In his fascinating and eminently readable new book, Stolen Words: The Nazi Plunder of Jewish Books (Jewish Publication Society, 2016), Rabbi Mark Glickman reminds us that Jews have always relied on books as essential sinews, binding Jews to God, to each other, and to the rest of humanity, regardless of time or space. He writes,

“To destroy a book is to sever the bonds it creates... to bring the stories that it tells… to an abrupt and irreversible halt… to extinguish the hope of discovery that its boundless riches can offer.”

The first part of Stolen Words is a love story between the Jewish people and books, whether etched in stone, written on parchment scrolls, or printed in ink. Through the centuries before books were mass-produced, they were valued works of art. Scribes spent countless hours creating each unique work. Even in our age of e-books, many families continue to treasure inherited antique books as heirlooms, their musty pages bearing the faint aroma of a grandfather’s cigar, a flowery inscription from a long-deceased relative, faded smudges of ancestral thumbs. The books on our shelves, Rabbi Glickman observes, also “testify to the intellectual and literary scope of their owners” and imbue them with something of the author’s essence.

The Nazis were not the first to condemn Jewish literature, Rabbi Glickman writes. The first recorded incident of Jewish book destruction occurred in the second century B.C.E., during the Hasmonean revolt. We read in I Maccabees (1:56-57):

“The books of the law which [the soldiers of Emperor Antiochus IV] found they tore to piece and burnt with fire. Where the book of the covenant was found in the possession of anyone, or if anyone adhered to the law, the decree of the king condemned him to death.”

In 1239, Pope Gregory IX ordered Christian rulers throughout the world to confiscate all copies of the Talmud found to contain any blasphemous content and burn them. Some Christian leaders ignored the Pope’s decree, but in France, long a center of Jewish learning and scholarship, King Louis IX ordered Jews to surrender every copy of the Talmud in their possession on a specified day. Jewish leaders appealed to the Archbishop of Sens, who successfully interceded with the king on their behalf.

One year later to the day, the Archbishop dropped dead as he entered the king’s chamber. Taking this as a sign of divine retribution and fearing he would suffer the same fate, King Louis IX reissued his confiscation order. In 1242, more than 20,000 copies of the Talmud were heaped together in the main square of Paris and set ablaze. Forty-two years later, in 1290, the throne issued an edict expelling all Jews from France.

Enemies of the Jewish people have long understood that books are the repositories of a people’s ideas and culture. Destroying Jewish books is to mock “the people of the book,” to deprive them of an essential source of ethnic pride, and to eclipse a competing civilization. The Nazis took it even further, making cultural denigration a prelude to genocide.

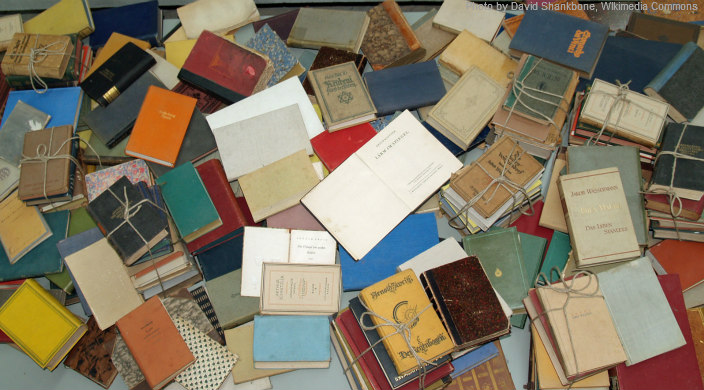

At its core, Stolen Words is the story of the tens of millions of books looted by the Nazis from Jewish homes, libraries, schools, and synagogues. Though the Nazis did stage elaborate book burnings for propaganda purposes, their end-game, unlike that of anti-Semites before them, was not censorship or to force Jews to renounce their religion and convert. Rather, they wanted to preserve Jewish books as relics of an extinct people and as a testament to German cultural superiority. Ironically, after the fall of the Nazis, the Jewish literature they had amassed affirmed the greatness of Jewish thought and scholarship.

Upon discovering these troves at the end of World War II, the Allied Forces eventually entrusted the books to Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc., an organization of leading Jewish scholars headed by the distinguished Jewish historian, Salo Baron.

Many of these rescued books, like the saved Holocaust Torah scrolls in London housed in synagogues throughout the world, will occupy an honored place in Jewish history. Long after the last human survivor is no longer here to tell the story, Jewish books, including Stolen Words, will help us, in the words of the author, “to keep faith with the past and sustain hope in our future.”

Related Posts

Harnessing the Power of our Mothers Around the Seder Table

Melding Tradition and Innovation: Our Interfaith Toddler Naming Ceremony