"Tell me a story" is a constant refrain for those of us with children in our lives. Almost as often, when the last page is turned, the child looks up and asks, "again?" Sometimes, this is a joy - Erica never tires of reading "Eloise" in a bratty kid voice to her daughters. Sometimes, re-reading, and re-reading some more, becomes a burden - in desperation, Leah resorted to hiding her niece's copy of Chris Barash's 2018 book "Is it Rosh Hashana Yet?" after her niece made her read it four times in a row one afternoon. Regardless, repetition is part of the storytelling process.

Humans are story-telling creatures the way birds are nest-building creatures or spiders are web-spinning creatures. On Simchat Torah, we read the last page of our people's sacred story. Then, without even pausing for breath, we go right back to the beginning, and start the story all over again. We need these stories, ancient and complicated as they are. We need to repeat them because we're human. We build our worlds out of stories and live in them by telling them over and over again.

When the First Temple was destroyed in 586 BCE, we gathered our stories around us like they were rocks and stones that could shelter and support us. It became our tradition to gather every week to study our people's stories, interpret them, and apply them to our lives. We kept doing that year after year. When we reached the end of those stories, we turned them over, unrolled the scroll, rerolled it back to the beginning, and reinterpreted them. We came back to Jerusalem, gathered stone and wood again, and rebuilt. We retold the stories, watched our Second Temple crumble, regathered our stories, reinterpreted them, and added a few new ones.

Week after week and year after year, whether in our houses, on the , or in the classroom, we kept building this temple of stories around ourselves.

When we live in something for thousands of years, we need to do constant maintenance, like making frequent repairs and adding occasional updates. Repeating, repairing, and updating stories can be its own pleasure. Leah's niece goes wild for Mo Willem's "Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs," a delightful spin on the old classic with a decidedly different moral. New interpretations can also be a necessity: sometimes an ancient story clashes with our modern mindset or even causes harm. Judaism has its own tradition of updating and repairing our stories -, from the Hebrew root dalet-resh-shin, meaning "to explore, investigate, and inquire."

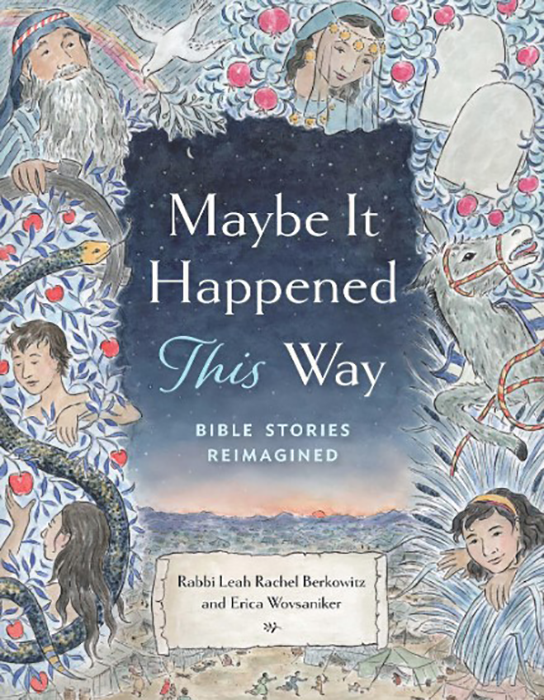

As we begin the cycle of sacred storytelling again, we are excited to introduce our book of middle-grade midrash, "Maybe It Happened This Way: Bible Stories Reimagined." We hope it will introduce young readers to the concept of midrash, which many call "biblical fan fiction." Just like fan fiction takes parts of canonical stories and makes them more relevant or engaging, the process of midrash can encourage readers to step into these ancient stories and see what meaning we can gain from them today.

We often rely on midrash to fill in the gaps in the biblical narrative and make these stories come alive for our generation. While there are anthologies upon anthologies of midrash for us to choose from, we still found that certain characters were being overlooked and that certain kinds of stories weren't being told, especially the stories we wanted to tell as Reform Jews, feminists, and teachers who value diversity and inclusion.

We wanted to create midrash that would feature some of the lesser-told stories in the Torah while providing a new perspective on some of our old favorites. Our editors challenged us to make at least one midrash for every book of the Torah, dealing with tricky Levitical topics like tzara'at - a biblical skin disease - and azazel, the mysterious Yom Kippur ritual of releasing a goat into the wilderness.

This was a collaborative effort, not only between the two of us and our editors, but with the original storytellers who brought us the Torah and the generations of rabbis who wrote midrash thousands of years ago. We also hope to collaborate with students and teachers who read this book and decide to create some midrash of their own!

We wrote "Maybe It Happened This Way" because we want children - in our families, in our classrooms, and young people the world over - to understand that midrash is always happening and they can do it, too. We want them to know that even though some of the words of our tradition are "set in stone," we can always add more stones.

Related Posts

The Power of Words: Cory Silverberg Writes a Better World into Existence

Decreasing Isolation, Celebrating Individuality: An Interview with Nomi Ellenson